Domestic Poverty

Can stricter work mandates reduce the poverty rate?

By Kay Nolan, January 11, 2019

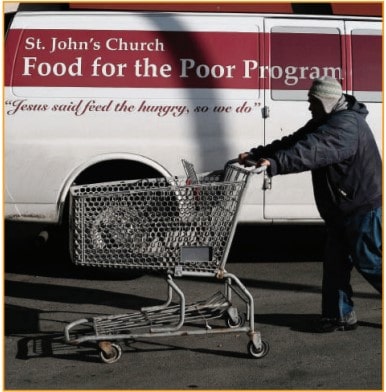

A man enters a soup kitchen in Worcester, Mass., where

the poverty rate is higher than the national average. Some

40 million Americans live in poverty, according to the

most recent census data, and the U.S. poverty rate is 12.3 percent.

A decade after the 2007-09 financial crisis and the weak recovery that followed, the U.S. poverty rate has reverted to prerecession levels, but extreme poverty is worsening.

Economists attribute this situation to widening

income disparity, wage stagnation, a scarcity of affordable housing and the growing prevalence of part-time or temporary employment.

Natural disasters and other economic disruptions also worsen the plight of the poor. Liberals and conservatives remain divided on the severity of poverty and how to reduce it. While they agree that government safety net programs have helped lift many Americans out of poverty, conservatives want to increase work mandates with the goal of reducing the number of people receiving government assistance.

The Trump administration and many Republicans say requiring the able-bodied poor to meet stricter work requirements in return for assistance is the best way to reduce poverty. But Democrats say most able-bodied poor people already are working and that added work mandates fail to address the root causes of poverty. They call for increased spending on aid and more and better job-training programs.

The Issues

For Antione Dobine, poverty is a constant companion.

The 49-year-old lives with his wife, Nina Stoner-Dobine, and five children, ages 11 to 19, in a two-bedroom apartment in Chicago’s West Pullman neighborhood.

Work these days consists of stints as a youth sports referee and an events host, at which Antione Dobine makes $1,200 to $1,400 per month.

After paying monthly rent of $750, he has little left to support his family.

Health issues prevent his wife from working, and her application for Social Security disability benefits is pending.

“I make enough to pay for my rent, the lights, my phone, maybe a few clothes for the kids, but anything extra, no. I’m broke until the next month,” Dobine says.

Dobine is among a rising number of Americans in “deep poverty” — those with incomes less than half the poverty threshold, which is $38,173 for a family of seven.

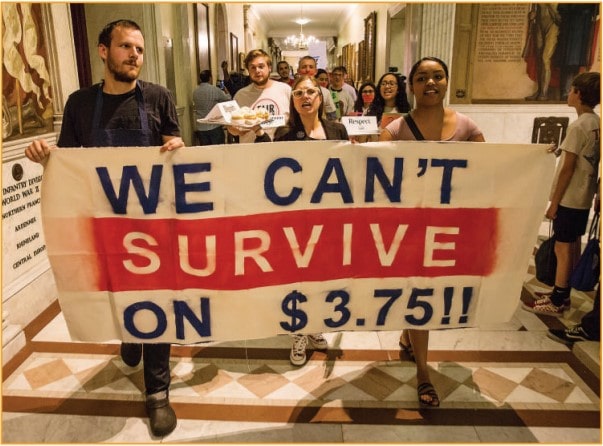

Restaurant workers in Boston protest in June 2018 against a law allowing

employers to pay workers who receive tips less than the federal minimum wage

of $7.25 an hour. Overall, the average hourly wage nationwide has the same

purchasing power as in 1978.

A decade after the 2007-09 financial crisis and its prolonged aftermath, the economy is growing and the unemployment rate has fallen to 3.9 percent. Yet some 40 million Americans live in poverty, and the poverty rate remains stubbornly high at 12.3 percent where it was in 2006. Deep poverty is at a 20-year high,

with nearly 20 million Americans classified as severely poor.

Economists attribute poverty’s persistence to a growing income disparity, wage stagnation, a scarcity of affordable housing and an increasing shift in employment practices toward part-time or shortterm jobs.

“[The poor] are becoming a more deprived and destitute class, one that’s disconnected from the economy and unable to meet basic needs,” said United Nations special rapporteur Philip Alston, who issued a report in December 2017 on U.S. poverty. “The face of poverty in America is not only black, or Hispanic, but also white, Asian and many other colors.”

Although poverty is found in all groups, “African-Americans, Latinos and Native Americans are poor at close to three times the rate of whites,” Peter Edelman, who was an assistant secretary in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services under President Bill Clinton, wrote in 2012. “This disparity raises obvious questions of discrimination, both overt and more subtle, embedded in the functioning of such systems as schools and criminal justice.”

Children also suffer disproportionately: The poverty rate for those under age 18 is 17.5 percent, nearly double that for those over age 64.

In an era of bitter political warfare, conservatives and liberals remain far apart on how — and how much — to help needy Americans.

The Trump administration and congressional Republicans believe the best approach is to require more of the poor to work in return for assistance because employment can help them escape poverty. That approach, they say, also would lower the cost of poverty programs, which totaled $729 billion in 2017, because people would theoretically need less assistance. The White House Council of Economic Advisers said in July that the so-called War on Poverty — a national effort to eliminate poverty begun during the 1960s — “is largely over and a success,” and that the federal government should promote self-sufficiency by expanding workrequirements, which have existed for “able-bodied” recipients since 1996.